You know that weird feeling. You wake up, and for exactly three seconds, you’re still there. You were flying over a neon-lit Tokyo, or maybe you were having a deeply intense conversation with a talking cat about your high school algebra grade.

It was vivid dream. It was cinematic. It felt important.

And then—poof.

It’s gone. By the time you reach for your phone or try to tell your partner about it, the edges start to fray. The colors fade to grey. The plot makes no sense at all. It’s like trying to hold a handful of water; the tighter you squeeze, the faster it leaks through your fingers.

Honestly, it’s kind of a tragedy, isn’t it? We spend about a third of our lives asleep. That’s decades of “content”—wild, uninhibited, Oscar-worthy stories generated by the most powerful supercomputer in the known universe (your brain), and we just… let it delete itself every morning.

But what if we didn’t have to?

What if you could wake up, hit “Sync” on a bedside device, and cast last night’s REM cycle directly to your TV while you drink your morning coffee?

It sounds like pure sci-fi—something pulled straight out of Inception or Black Mirror.

But here’s the thing: we’re actually a lot closer than you might think. We aren’t just dreaming about recording dreams anymore. We’re building the cameras.

So… Where We Are Right Now?

I want to be real with you: we aren’t at the “4K Blu-ray” stage of dream recording yet. If I told you we were, I’d be brutally lying. Right now, we’re more in the “grainy, black-and-white, silent film from 1895” stage. But even that is a miracle when you think about it.

How do you actually “see” a thought? That’s the enigma scientists have been trying to crack for decades. Currently, the gold standard is something called fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging).

You’ve probably seen these machines. They look like giant, expensive donuts that you slide into. They measure blood flow in the brain. When a specific part of your brain works harder, it needs more oxygen, and the fMRI catches that “light up” moment.

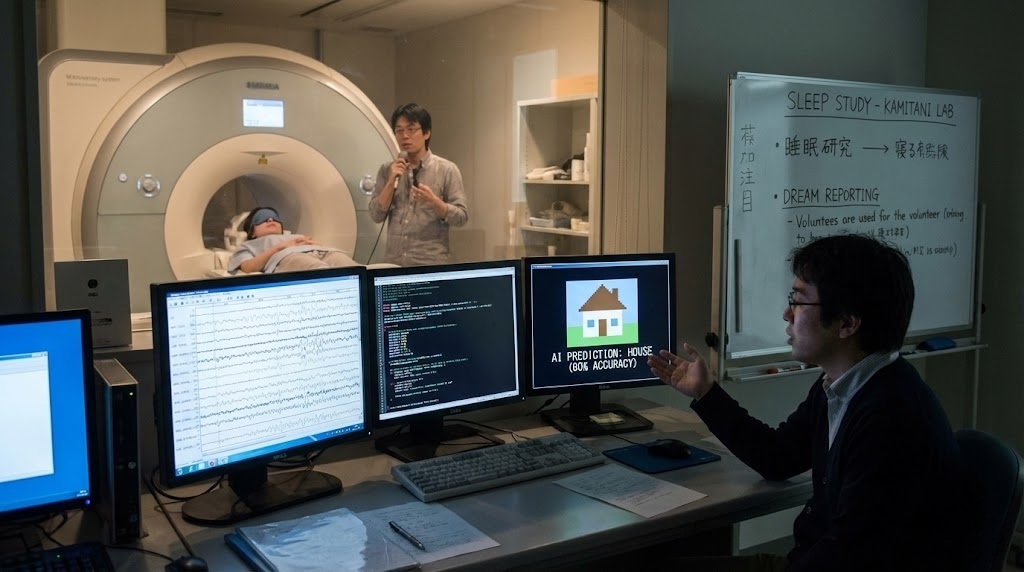

The Japanese Breakthrough

Back in 2013, a team in Japan, led by Yukiyasu Kamitani, did something that shifted the entire landscape of neuroscience. Well, kind of. Namely, they put people in these scanners and let them fall asleep. Every time the brain patterns showed they were starting to dream, the researchers woke them up and asked, “What did you see?”

They did this hundreds of times. (Think about those volunteers—that has to be the most annoying night of sleep in human history.)

They used all that data to train an AI.

They taught the computer: “Look, when the brain looks like ‘X,’ the person is seeing a house. When it looks like ‘Y,’ they’re seeing a street sign.”

Eventually, the AI got good enough that it could look at the brain scans of a sleeping person and guess what they were dreaming about with about 60% accuracy.

It wasn’t a movie yet—it was more like a game of neural Pictionary. The AI would say, “I see a man… a building… something made of wood.” And the dreamer would wake up and say, “Yeah, I was in an office.”

Reconstruction: Pulling Faces from the Mind

Fast forward to today, and we’ve moved past simple objects. Researchers at the University of Oregon and other global labs have moved into “Neural Decoding.”

They showed people photos of faces while they were in a scanner. The AI watched how the visual cortex reacted to a nose, an eye, a chin. Then, and this is the spooky part, they showed the AI only the brain activity and asked it to reconstruct the face the person was looking at.

The results look like something out of a ghost story.

They’re blurry, shifting, and ethereal. You can tell it’s a human face, but it looks like it’s being reflected in a rippling pond. But hey, it’s a start. And a big one.

It’s the first time we’ve ever reached into a human skull and pulled out an actual image.

The AI “Director”: How Sora and Stable Diffusion Saved Dream Tech

But wait, it gets even cooler. If we’re going to talk about turning dreams into movies, we have to talk about the “engine” under the hood. Currently, the most exciting stuff isn’t just happening in biology; it’s happening in AI labs.

You’ve probably seen those AI video generators like Sora or Veo. They’re mind-blowing. You type in “A golden retriever wearing a space suit on Mars,” and it spits out a video that looks like a big-budget movie. Well, researchers are now realizing that these AI models are the “missing link” for dream recording.

So, what is happening now? Well…

The Secret Sauce: Latent Diffusion Models (LDM)

Scientists aren’t trying to record your brain like a VHS tape anymore. They’ve realized that’s impossible because the brain is too “noisy.” Instead, they’re using something called Latent Diffusion Models.

Think of it like this: If you tell a talented artist, “I saw a blurry red shape that felt like a car,” the artist doesn’t just draw a blurry red blob. They use their knowledge of what cars look like to paint a beautiful, crisp Ferrari.

That’s exactly what models like NeuralFlix (a research project name) are doing. They take the messy, low-resolution signal from an fMRI, which might just say “vague motion” and “red”, and they feed it into a video diffusion model. The AI acts as the “director.”

It says, “Okay, I see the brain is perceiving a high-speed chase. I’ll use my internal database of millions of hours of video to render a sharp, cinematic version of that thought.”

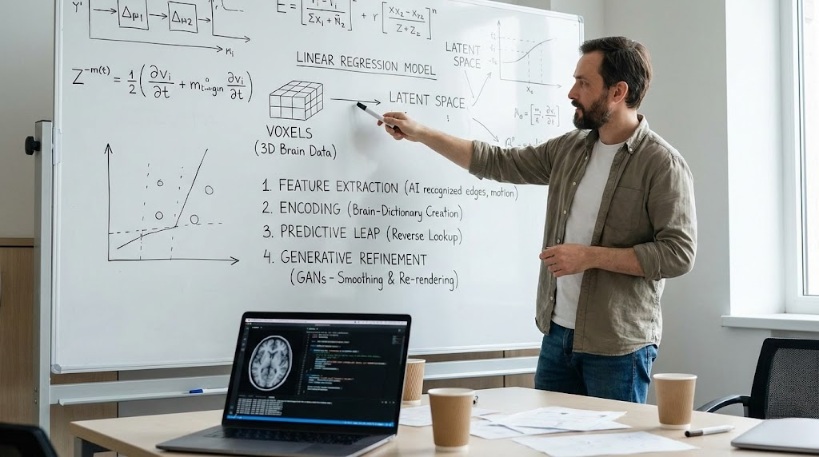

And so… What Is The Math Under the Hood?

If you’re still with me, you’re probably wondering how exactly a computer translates a blood-flow spike into a pixel. Look, the math is complex, but the concept is actually pretty elegant.

Researchers use Linear Regression Models to map “voxels” (3D pixels of brain data) to “Latent Spaces” in AI.

- Feature Extraction: An AI model is shown thousands of hours of video and learns to recognize features like “edges,” “shadows,” and “motion vectors.”

- Encoding: While a human watches these same videos, a scanner records how their neurons fire in response to those specific features. This creates a “dictionary” of the person’s brain.

- The Predictive Leap: When you dream, the process is reversed. The AI looks at your brain’s current activity and searches its dictionary. “Aha! This pattern usually means ‘upward movement’ and ‘blue hues’.”

- Generative Refinement: A Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) then “smooths” these predictions. It fills in the gaps so that instead of a flickering mess, you get a coherent video stream. It’s not just “recording” the dream; it’s re-rendering it based on your neural prompts.

The Hardware: What Will We Actually Put in Our Heads?

Okay, let’s talk engineering. If we want to move past those giant, clunky MRI machines, what does the actual hardware look like? To get a movie-quality recording, we need a way to listen to millions of neurons at once without ruining our lives.

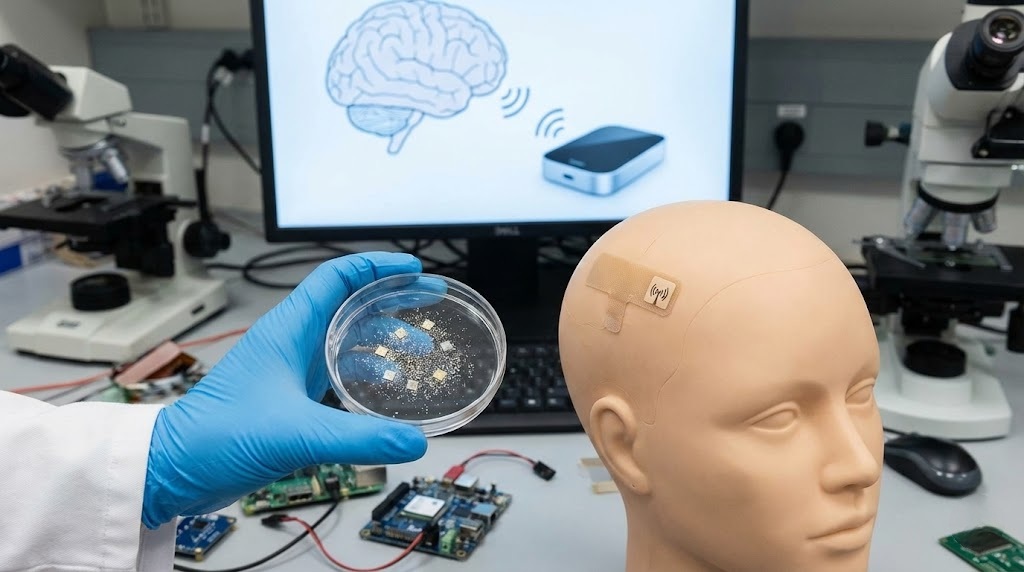

1. The “Neurograin” Mesh (The Tiny Surgeons)

Imagine a “dusting” of sensors. Researchers at Brown University and other labs are already working on something called Neurograins. These are tiny, salt-grain-sized microchips that can be sprinkled across the surface of the brain.

They don’t need wires. They power themselves wirelessly through the skull using a thin, wearable patch (like a smart-bandage) on your scalp.

While you sleep, they act like a massive, distributed microphone, picking up the “whispers” of your neurons and beaming them to your bedside hub. This hub then does the heavy lifting of turning those whispers into a 4K video file.

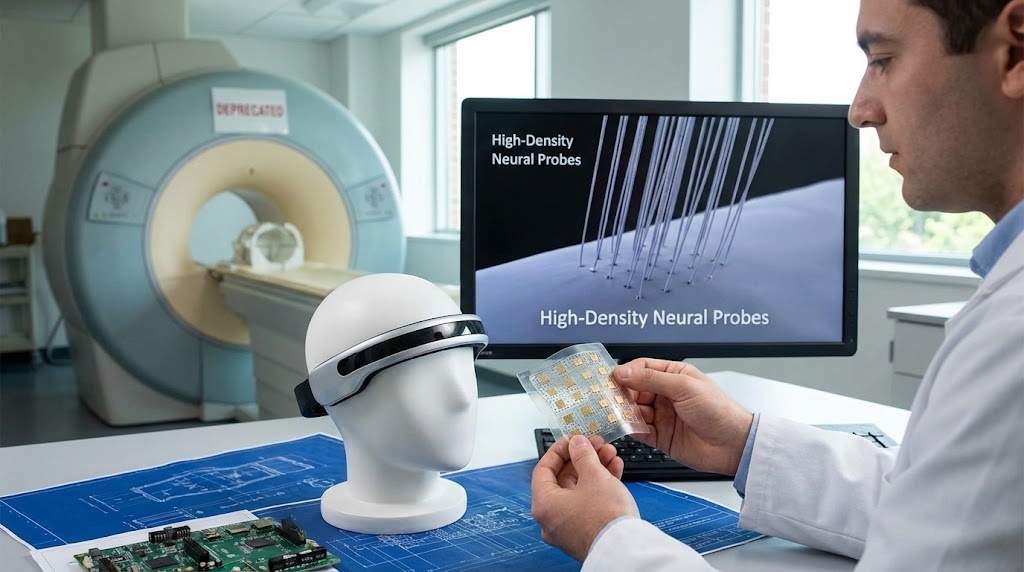

2. The High-Density Neural Probe (The Brain Stitch)

We’ve all heard of Neuralink, but the real magic there isn’t the chip; it’s the threads. They use a “sewing machine” robot to insert ultra-thin, flexible electrodes into the brain.

For dream recording, a future version of this might involve millions of microscopic “hairs” that weave into the folds of your brain. Because these are inside the tissue, the signal is crystal clear.

No noise.

It would be like the difference between listening to a concert through a wall versus wearing high-end noise-canceling headphones. This would give the AI the “RAW” data it needs to reconstruct every single detail of your dream—down to the texture of the leaves on a dream-tree.

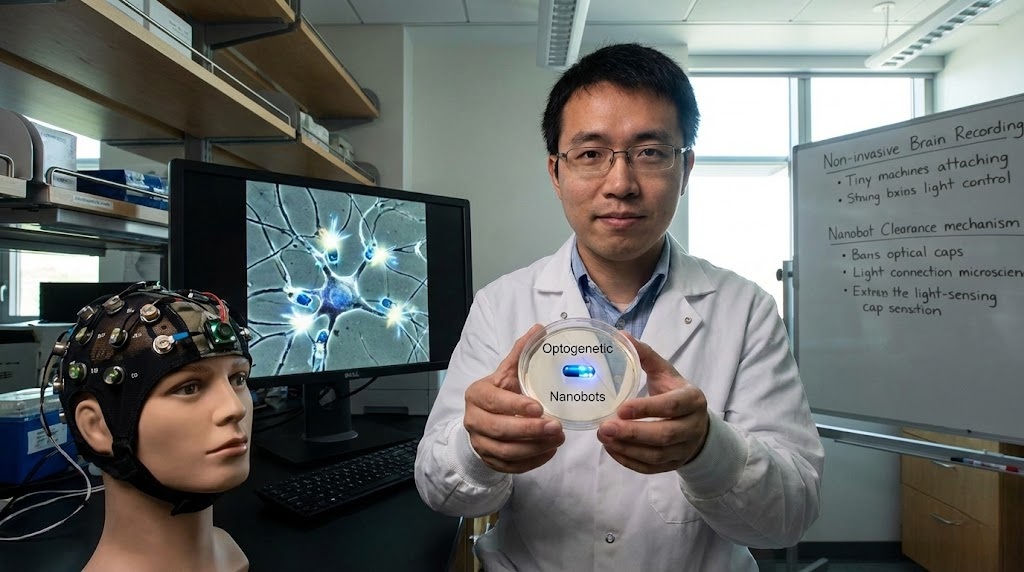

3. Optogenetics & Nanobots (The “No-Surgery” Holy Grail)

This is the “way out there” stuff, but it’s based on real science. Imagine taking a specialized pill filled with nanobots (tiny biological machines). These nanobots travel to your brain via the bloodstream, attach themselves to specific neurons, and emit a tiny flash of light every time that neuron fires.

You’d wear a “light-sensing” cap while you sleep that captures these microscopic flashes through your skull. It sounds wild, I know.

But it would be completely non-invasive. Once the “recording session” is over, your body would naturally flush the nanobots out.

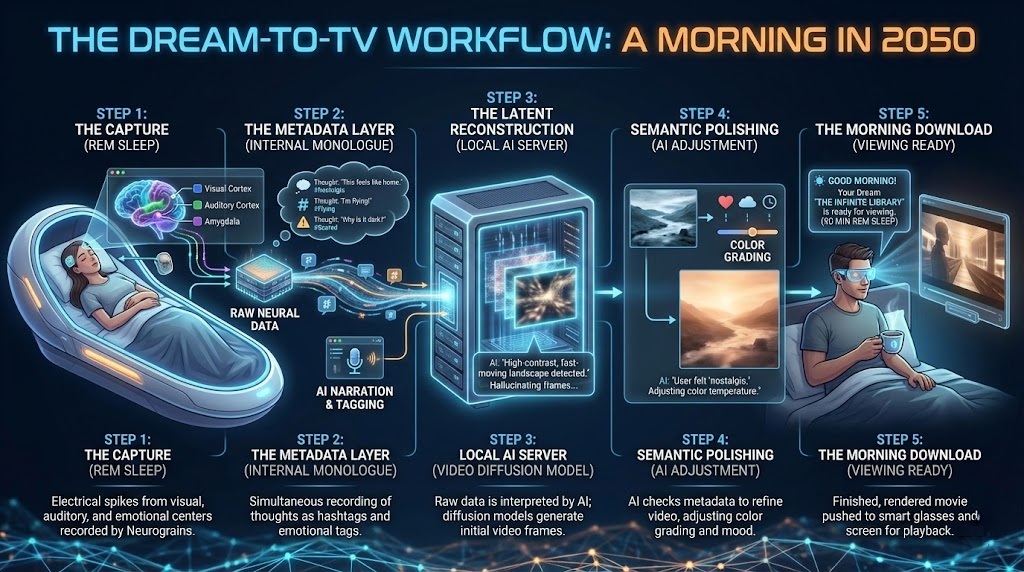

The Dream-to-TV Workflow: A Morning in 2050

If you were to look under the hood of the process in the year 2050, it would most likely look like this five-step pipeline:

- Step 1: The Capture. You enter REM sleep. Your brain starts firing. The “Neurograins” or probes pick up the electrical spikes in your visual cortex (what you see), your auditory cortex (what you hear), and your amygdala (how you feel).

- Step 2: The Metadata Layer. Simultaneously, the device records your “Internal Monologue.” Dreams are often “narrated” by our own thoughts. The AI records these as “tags”—sort of like hashtags for the video. (#Scared, #Flying, #ThisIsMyChildhoodHome).

- Step 3: The Latent Reconstruction. The raw brain data is sent to a local AI server. The AI looks at the visual signals and says, “I recognize these patterns; they represent a high-contrast, fast-moving landscape.” It uses a Video Diffusion Model to start “hallucinating” the frames that match those patterns.

- Step 4: Semantic Polishing. The AI then checks the “Metadata” layer. “Oh, the user felt ‘nostalgic’ here,” it notes. It adjusts the color grading of the video to be warmer and softer.

- Step 5: The Morning Download. You wake up. The AI has finished “rendering” the 90 minutes of REM sleep you had. It pushes a notification to your glasses: “Your Dream ‘The Infinite Library’ is ready for viewing.”

Three Scenarios: How You’ll Consume Your Dreams

I like to imagine how this tech will actually land in our laps. It’s rarely a giant leap; it’s usually a slow crawl of “Oh, that’s neat” until suddenly, our lives are unrecognizable.

Scenario A: The “Dream Journal” Headband

Imagine a sleek, fabric headband you slide on before bed. It’s the “Oura Ring” of the 2040s. It doesn’t give you a full movie, but when you wake up, your phone has a “Highlight Reel.” It’s a series of AI-generated images based on your neural peaks. You scroll through your app and see: A snowy mountain. A blue car. A face that looks suspiciously like your ex. It’s a visual dream journal.

Scenario B: The “Neural Stream”

This is for the early adopters. You have a small, non-invasive implant or a highly advanced “sleep cap” that uses room-temperature superconductors to read your brain waves with pinpoint precision. Because the AI knows your personal “brain language,” it can reconstruct a 3D environment. You put on a VR headset and re-enter the dream as an observer. You can walk around the dinner party your subconscious hosted last night.

Scenario C: The “Shared Cinema”

Imagine a “Dream Stream” where you and your partner can record your dreams and, if you both give permission, the AI merges them. You could watch the “movie” of your shared night together. Or, more likely, you’d have “Dream Creators”—artists who train themselves to lucid dream, “film” incredible surrealist epics in their sleep, and then sell the recordings on the 2060 version of YouTube.

But, Why Is This Harder Than It Looks?

I want to be really sincere here. As much as I want to watch my dreams on Netflix, there’s one huge biological hurdle: Dreams aren’t actually “videos” in the first place.

When you look at a tree in real life, your eyes send a constant stream of data to your brain. It’s a “bottom-up” process. But when you dream of a tree, it’s a “top-down” process. Your brain isn’t “seeing” anything; it’s remembering the concept of a tree and stimulating your visual cortex from the inside out.

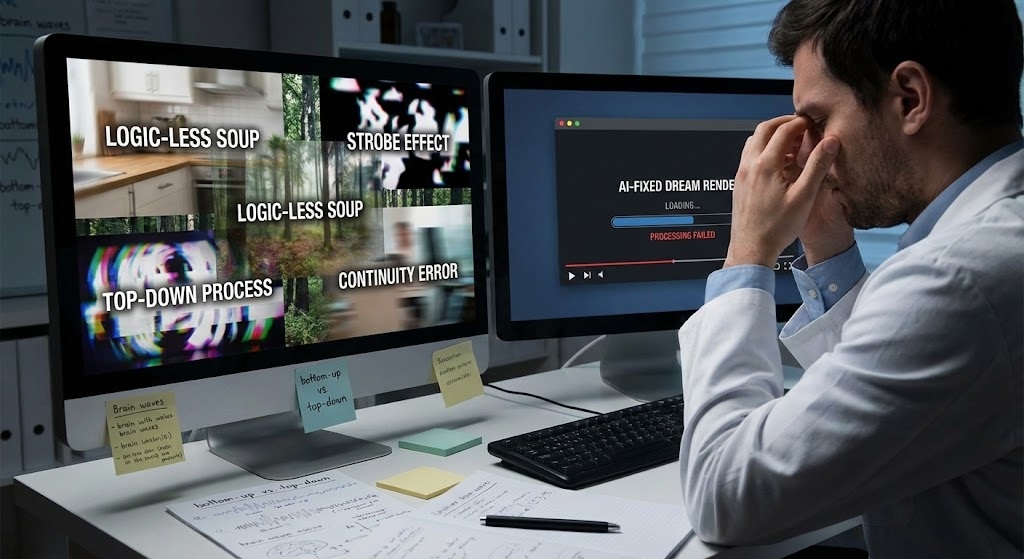

This means a dream is often a “logic-less” soup. In a dream, you can be in your kitchen, but you turn around and you’re in a forest. To our brains, this makes perfect sense.

But to an AI trying to render a “movie,” this is a nightmare of “continuity errors.”

If we record our dreams exactly as they happen, the “movie” might be unwatchable. It might be a flickering, nauseating strobe-light of shifting images.

To make it a “movie” we actually want to watch, the AI has to “fix” the dream. It has to add a beginning, a middle, and an end.

And that leads to a deep philosophical question: If the AI “fixes” your dream to make it watchable, is it still your dream? Or is it a collaboration between your subconscious and a machine?

What We Can Do Right Now (The Human Side of the Science)

We don’t have the headbands yet, but you actually have a “built-in” recorder that most of us never use. It’s called Lucid Dreaming and Targeted Memory Reactivation.

Brain Scanning as a “Mirror”

Even with today’s “grainy” fMRI tech, we’re using brain scanning to help people with Nightmare Disorder. Scientists can play a specific sound (like a gentle piano chord) while you’re learning something during the day, and then play that same sound while you’re in REM sleep. It “nudges” your brain to dream about that specific topic. We’re essentially starting to “edit” the script of our dreams before they even happen.

The “Thought-Typing” Bridge

There’s also work being done with Non-Invasive Brain-Machine Interfaces that allow people to “type” just by thinking. Some researchers are trying to use this for “Dream-Typing.” Instead of a full movie, the device detects the concepts you’re thinking about and types them out into a text file. You wake up to a “script” of your dream: “I was at a beach… the water was purple… I felt like I was searching for a key.” It’s not a Netflix special, but it’s a start. You’re training your brain to bridge the gap between the sleeping world and the waking one.

So… In Our Lifetime?

Are we going to be watching “Dream Movies” by next Tuesday? No. But are we on a collision course with a world where the boundary between “thought” and “digital media” disappears? Absolutely. Within our lifetime, “I forgot my dream” might become a phrase as obsolete as “I’m lost” (thanks, GPS) or “I don’t know the answer” (thanks, Google).

We are going to become the directors of our own midnight cinema. And honestly? I can’t wait to see what’s playing on your screen.

So, here’s a question for you: If you could record just one dream from your past to watch tonight on your TV—which one would it be? And would you let anyone else watch it with you?