Philosophy is never meant to be comfortable. Sometimes it’s complicated, sometimes it’s rather weird, but in many cases, it is there to question something (or someone).

Throughout history, some philosophers have pushed the envelope so hard that that philosophy turned into something else.

These philosophers didn’t just challenge ideas; they pulverized them, leaving behind a legacy that is brilliant but also controversial in one way or another.

And so – what actually makes a philosopher controversial? It’s not just about having wild ideas—it’s about being fearless enough to say what others won’t, even if it earns you enemies or costs you your reputation.

Some flirted with the dark side, getting tangled up in political regimes, drugs, or morally questionable lifestyles. Others made their name by putting a middle finger at religion, morality, and the very foundations of civilization.

These five philosophers fit the bill perfectly—each more provocative, bizarre, and sometimes darker than the last.

So let’s begin – let’s explore those brilliant but sometimes weird minds.

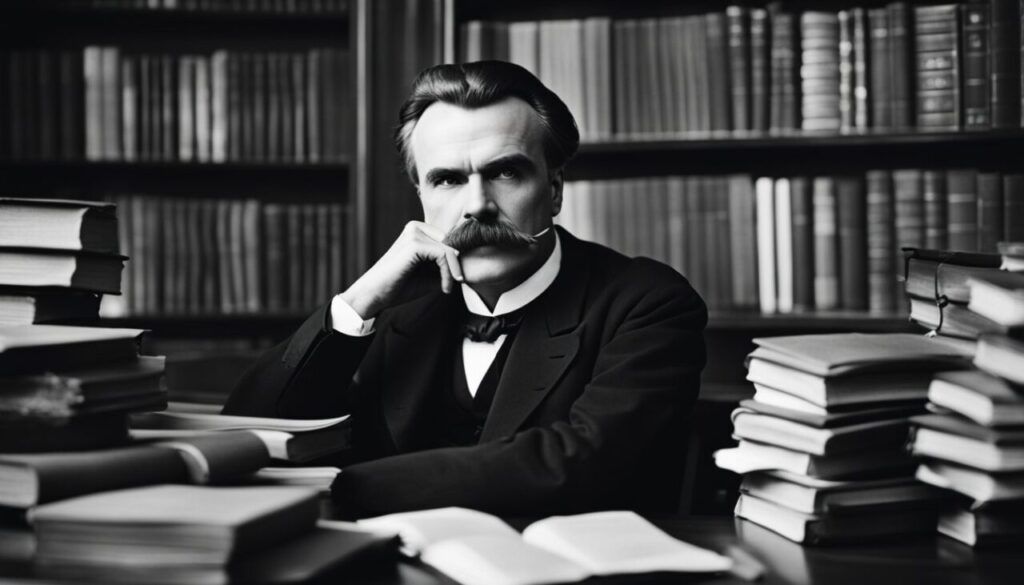

Friedrich Nietzsche

Let’s start with Friedrich Nietzsche, the philosopher who went from raging critic of religion to—quite literally—losing his mind.

If you’ve heard anything about Nietzsche, it’s probably that he declared, “God is dead,” and sent shockwaves through the religious world.

But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Nietzsche didn’t just go after God—he attacked Christianity, morality, and everything that made people feel “comfortable.” To him, organized religion was nothing but a crutch for weaklings.

Nietzsche’s philosophy revolved around his concept of the Übermensch or “superman,” a future being who would rise above conventional morality.

But his critics accused him of laying the groundwork for some of the most horrific regimes in modern history.

Though he himself never promoted violence, some saw echoes of his ideas in the rise of Nazi ideology.

Nietzsche, for his part, spent his last years semi-insane, raving about eternal recurrence, while his sister twisted his words into propaganda for the far right.

Here are some additional bits of strangeness attached to Nietzche:

· The “Horse Incident”: In 1889, Nietzsche witnessed a coachman beating a horse in the streets of Turin, Italy. He ran to the horse, threw his arms around its neck, and sobbed uncontrollably. This emotional collapse is often seen as the breaking point where Nietzsche’s mental health deteriorated, leading to his complete mental breakdown. He spent the remaining 11 years of his life in a state of madness, under the care of his mother and sister.

· Obsession with Richard Wagner: Nietzsche had an intense admiration for the composer Richard Wagner and his music. At first, they were close friends, and Nietzsche saw Wagner’s work as the embodiment of his philosophical ideals. But things soured after Nietzsche grew disillusioned with Wagner’s increasing religiosity and nationalist leanings. Their split was dramatic, and Nietzsche’s later writings were filled with malice against his former idol.

· Lonely and Loveless: Despite being an influential thinker, Nietzsche struggled big time in his personal relationships. He proposed to the same woman, Lou Andreas-Salomé, multiple times, only to be rejected each time. He remained a bachelor for life, and many of his letters reveal a deep sense of loneliness. Some even speculate that Nietzsche may have died a virgin, despite his musings on love and relationships.

· Fear of Sunlight: Nietzsche had a strange phobia of sunlight and spent much of his time with blinds drawn, writing in dimly lit rooms. His poor health—especially his chronic migraines and failing eyesight—may have contributed to his aversion to bright light. His discomfort was so extreme that he often wore a wide-brimmed hat and dark glasses when outdoors.

Interesting fact: Nietzsche’s posthumous fame was largely shaped by his sister, Elisabeth, a hardcore nationalist who edited his works to align them with her racist, anti-Semitic ideology.

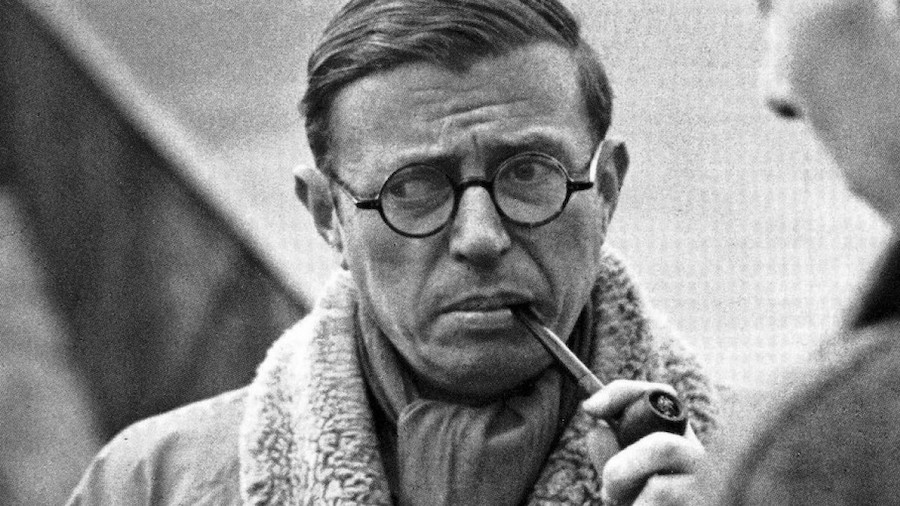

Jean-Paul Sartre

Sartre was an existentialist who argued that life has no inherent meaning. We’re born, we exist, and that’s it. Whatever meaning life holds comes from the choices we make.

Sounds liberating, right?

Well, until you realize that Sartre thought this freedom was also a curse. Humans, Sartre argued, are “condemned to be free”—burdened with the responsibility of shaping their own lives in a meaningless universe.

While that alone would make Sartre controversial, things get more interesting when you look at his politics. For a guy who preached personal freedom, Sartre had a soft spot for authoritarian regimes.

He openly supported Stalin’s Soviet Union, and later Mao’s China, despite knowing about the atrocities committed under both.

He even wrote off Soviet gulags as “necessary evils.”

Interesting fact: Sartre once took amphetamines for an entire year, writing the 650-page Critique of Dialectical Reason in a drug-fueled haze. He later admitted to seeing giant lobsters crawling behind him wherever he went.

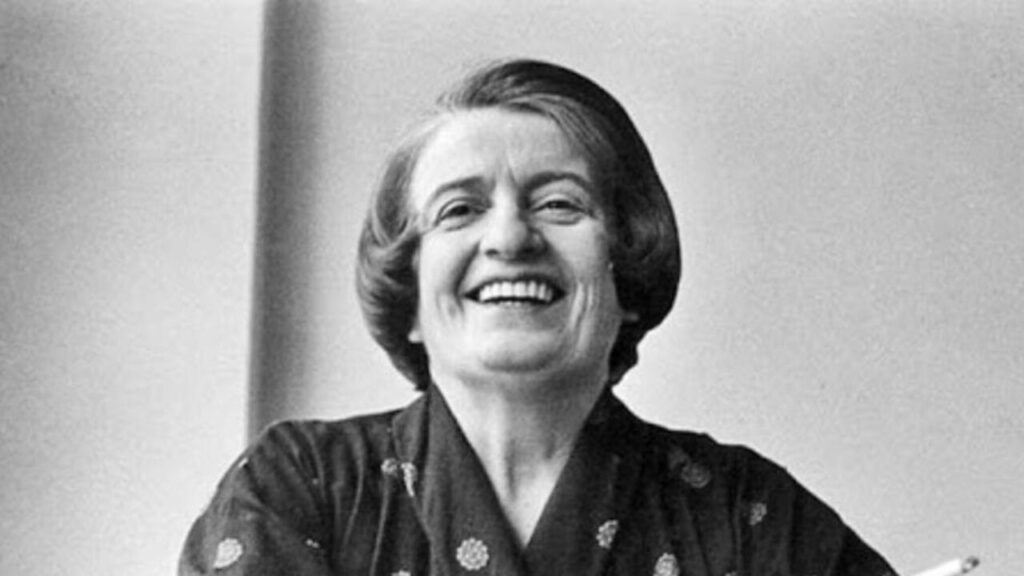

Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand was a philosopher who would be the poster child for late-stage capitalism—if she weren’t so divisive.

Her philosophy, Objectivism, is built around the idea that selfishness isn’t just good, it’s the highest virtue. Forget about helping others.

For Rand, the individual’s pursuit of their own happiness was the ultimate moral duty. Anything that got in the way of that—especially altruism—was a lie, an act of moral cowardice.

Her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, has been both applauded and criticized.

On one hand, it inspired generations of free-market capitalists and libertarians who believe in the power of the individual.

On the other, critics argue that Rand’s philosophy is little more than a justification for ruthless greed. But Rand didn’t care what her critics thought. She once said, “The question isn’t who is going to let me; it’s who is going to stop me.”

Rand’s personal life was a mess, too.

Despite preaching rational self-interest, she had a passionate love affair with a much younger man, Nathaniel Branden, which nearly destroyed her social circle.

When Branden eventually dumped her for a younger woman, Rand flew into a jealous rage.

Interesting fact: Ayn Rand demanded that all of her closest followers read Atlas Shrugged multiple times and even tested them on their knowledge of the book during dinner parties.

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault was a very interesting philosopher. He argued that power isn’t just something that kings or presidents hold—it’s everywhere, embedded in institutions like schools, hospitals, and prisons.

He was fascinated by how societies control people, not through violence, but through knowledge and surveillance. And we could easily agree with that. Society in many cases functions just like he described.

But Foucault wasn’t just an armchair philosopher. He lived on the edge, especially when it came to his personal life.

Openly gay, Foucault found intellectual and sexual liberation in San Francisco’s BDSM scene.

Some biographers even claim that Foucault contracted HIV in bathhouses and viewed his illness as a kind of philosophical experiment, pushing the boundaries of life, death, and bodily pleasure.

Foucault’s fascination with the Iranian Revolution also raised some eyebrows.

He initially hailed it as an uprising against Western imperialism and a sign of hope for new forms of power. What he didn’t anticipate was the theocratic dictatorship that followed.

Critics accuse Foucault of being blinded by his obsession with revolution, failing to see the authoritarianism lurking behind it.

Interesting fact: Foucault allegedly took LSD in Death Valley and claimed the experience profoundly influenced his thinking on power, madness, and the body.

Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger is probably the most controversial figure on this list—both for his ideas and his actions.

Heidegger is best known for his work on the nature of Being, captured in his dense, almost impenetrable book Being and Time.

He’s considered one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century, and his ideas have shaped existentialism, phenomenology, and even modern theology.

But here’s the thing: Heidegger was also a Nazi.

Not in a “he supported some questionable policies” way, but in a “he joined the party and served as rector of a university promoting Nazi ideology” way.

His involvement with the Nazi Party is a massive stain on his legacy. Even after World War II, Heidegger never fully apologized or recanted his Nazi ties.

To this day, people debate whether Heidegger’s philosophy is contaminated by his political affiliations.

Interesting fact: Heidegger was so obsessed with the concept of Being that he once said “Language is the house of Being.” This led some critics to quip that he might have been the world’s most famous “grammar Nazi.”