You know, it feels like we all just woke up one morning in late 2022, opened our laptops, and the world had changed. ChatGPT was there, generating poetry, writing code, and arguably understanding jokes better than some of our friends.

It felt sudden. Like magic. But here’s the thing about magic: it usually takes about seventy years of grinding, failing, arguing, and quiet breakthroughs to look like an overnight success.

If you’re here at Curious Matrix, you’re probably the type of person who isn’t satisfied with the “magic” explanation. You want to see the wires. You want to know how we got from a room full of vacuum tubes to a chatbot that can pass the Bar Exam.

The history of Artificial Intelligence isn’t just a timeline of inventions. It’s a huge story about (over)confidence, disappointment, curiosity, and a relentless obsession with understanding our own minds by trying to replicate them.

So, grab a coffee. We’re going to peel back the layers. This is the real story of how we taught machines to think.

Part I: The Dream Before the Data (Pre-1950s)

Before we had the microchip, we had the myth. Honestly, humans have been obsessed with AI long before we had the electricity to power it. If you look back at Greek mythology, you find Talos, a giant automaton made of bronze, created to protect Europa.

In Jewish folklore, you have the Golem, a being created from clay and brought to life through language (which is ironically (in one way) similar to how Large Language Models (LLM’s) work today).

We have always wanted to play God. We have always wanted to forge intelligence from lifeless matter.

The First Programmer

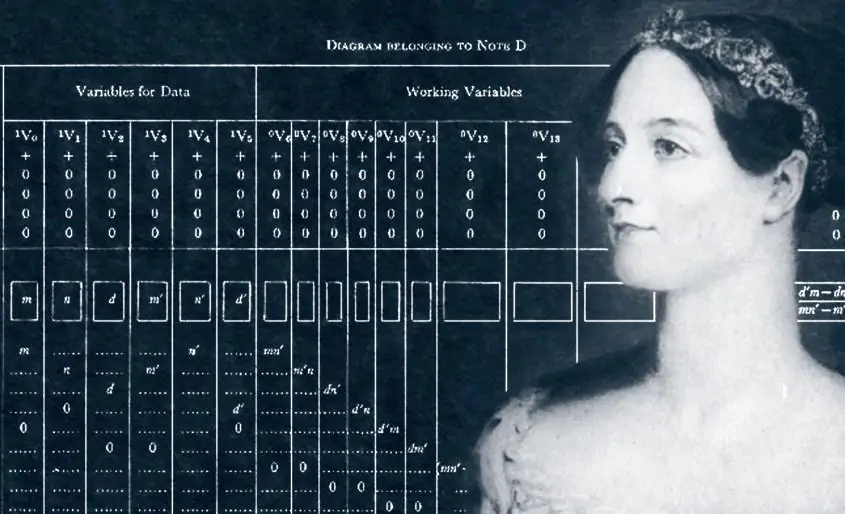

But if we’re looking for the actual grandmother of AI, we have to talk about Ada Lovelace.

Back in the 1840s, she was working with Charles Babbage on his “Analytical Engine” (a computer that was never fully built). While Babbage saw a super-calculator, Lovelace saw something else. She realized that if numbers could represent other things, like musical notes or letters, then a machine could theoretically compose elaborate pieces of music.

She called this “Poetical Science.” She famously wrote that the engine “has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.”

That quote haunted AI for a century. It was the first “skeptic” argument: Machines can only do what we tell them. They can’t create.

(Spoiler alert: She was right for about 170 years. And then, suddenly, she wasn’t. Well, kind of.)

Part II: The Birth of a New Science (1950-1956)

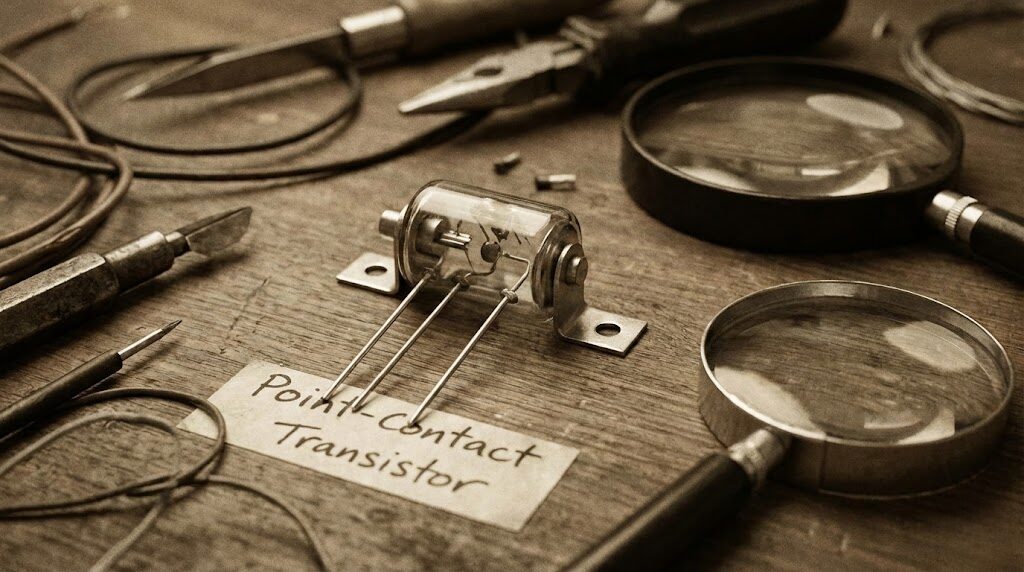

Fast forward to the aftermath of World War II. The world is rebuilding. The transistor is invented. And a man named Alan Turing asks a simple, terrifying question:

“Can machines think?”

In 1950, Turing published a paper called Computing Machinery and Intelligence. He knew “thinking” was too hard to define. So, he proposed a game. He called it the “Imitation Game.” You know it now as the Turing Test.

The logic was beautifully simple: If a machine can talk to you through a text terminal and fool you into thinking it’s a human 30% of the time, does it matter if it’s “thinking” or not?

If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, let’s just call it a duck.

The Dartmouth Workshop: The Summer of Optimism

If Turing provided the soul of AI, John McCarthy gave it a name. In the summer of 1956, McCarthy, along with Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon, organized a workshop at Dartmouth College.

We could easily say that this is arguably the most important event in computing history. And the proposal they wrote for it is absolutely hilarious in hindsight. They requested funding for a “2-month, 10-man study,” stating:

“We think that a significant advance can be made in one or more of these problems if a carefully selected group of scientists work on it together for a summer.”

They thought they could solve language, neuron synthesis, and abstract concepts in a summer.

They didn’t solve it. But they did coin the term “Artificial Intelligence.” They established the goal: creating machines that could solve problems that were previously reserved for humans. The field was born, and it was practically vibrating with optimism.

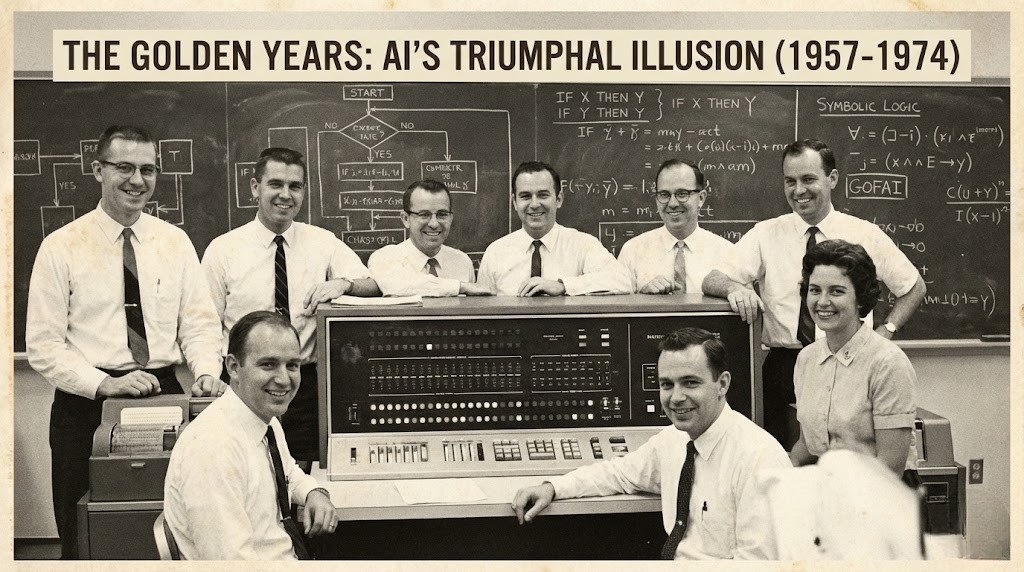

Part III: The Golden Years & The Illusion of Easy (1957-1974)

For the next nearly two years, it looked like the Dartmouth crew was right.

This era was dominated by something we now call Symbolic AI (or GOFAI – “Good Old-Fashioned AI”). The approach was top-down. The idea was that intelligence is just manipulating symbols (logic) according to rules.

If you could just program enough rules—If X happens, do Y—you’d have a brain. As so we had several triumphal stories.

The Success Stories

1. The Logic Theorist (1956)

The first real proof that this Symbolic AI idea might work came quickly with something called the Logic Theorist. It was built by Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, and Cliff Shaw.

Think about solving a math problem. You don’t just randomly plug numbers in until you get the answer, right? You eliminate the stupid choices first. You look for shortcuts.

That’s what the Logic Theorist did. It didn’t just brute-force calculations; it used heuristics, which is a fancy word for “rules of thumb.” It was designed to prove theorems from the mathematical classic Principia Mathematica.

And get this: not only did it prove 38 of the 52 theorems in the book, but for one of them, it found a more elegant proof than the one published by the actual human authors, Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead.

That’s a huge psychological win. A machine was reasoning. It was showing creativity, albeit in a narrow domain.

Simon was absolutely buzzing. He even famously claimed: “Machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do.” Can you feel that intense confidence? That’s what the early 60s felt like—everything was possible.

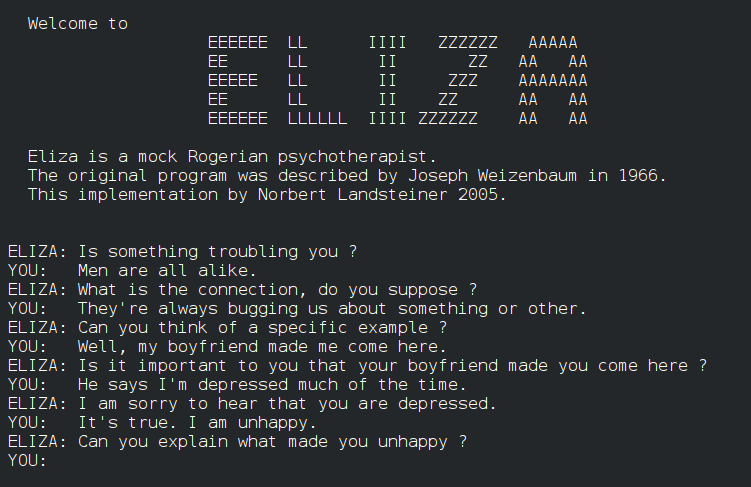

2. ELIZA (1966)

Now, let’s talk about the one that is truly wild: ELIZA (simple natural language processing program). Because the story of ELIZA is less about computer science and more about human vulnerability.

ELIZA wasn’t smart. Not at all. It was just a simple parlor trick created by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT. It was designed to mimic a Rogerian psychotherapist. This is the least demanding kind of conversation because the therapist usually just reflects your own words back at you.

It used a very basic pattern matching—no real understanding. If you typed, “My mother never understands me,” it would use a simple rule like, “If the sentence contains ‘mother,’ substitute ‘Tell me more about your mother.'”

But here’s the deeply human, slightly terrifying part, kind of a famous twist. Weizenbaum was horrified to find that people who interacted with his little program started taking it seriously.

He saw his own secretary, a woman who knew exactly how the code worked, talking to ELIZA. She’d start asking him to leave the room for privacy. She knew it wasn’t real, but the illusion of being heard was so strong she connected with it anyway. People would pour their hearts out to this simple piece of code.

This is the genesis of the “ELIZA Effect.” It’s our gut-level, emotional impulse to assign consciousness, empathy, and meaning to anything that mimics human conversation well enough.

Honestly, that effect is why ChatGPT is so successful today. The technology is massively more complex, yes, but the human desire to project and connect remains the exact same. We desperately want the machine to understand us.

3. Shakey the Robot (1966-1972)

Finally, we get to the OG autonomous bot: Shakey the Robot. Look, this „guy” wasn’t sleek. He was a moving computer on wheels with a big antenna, a TV camera, and tactile sensors—he looked like a fridge with a hat. But man, his brain was revolutionary.

Shakey was the ultimate test of Symbolic AI because he didn’t just follow pre-programmed instructions. He used a reasoning system (called STRIPS) to plan his actions.

If you told Shakey, “Go to Room A and push the large, blue box into the corner,” he didn’t have a prerecorded path. He would look around, consult his internal model of the world, and break the goal into sub-goals:

- Locate the box.

- Find a path to the box (checking for obstacles).

- Navigate to the box.

- Push the box.

If a chair was placed in his path after he started moving, Shakey wouldn’t crash; he’d update his internal map and find a new way around. Hereasoned about his own actions. He was, for a short time, the most intelligent machine ever created.

It proved that the Symbolic approach could, in theory, create an agent that interacted intelligently with the world. The catch, the fatal flaw, was that it only worked inside that one, controlled lab at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

Take Shakey outside, and the endless complexity of the real world would have instantly overwhelmed his fragile rule-set. But for that moment, in that controlled environment, it felt like the future had arrived. We had reasoning machines and emotional chatbots. It seemed so close… it seemed easy.

Funding was pouring in. The government (specifically DARPA) was throwing money at AI researchers like it was confetti. Researchers were making bold claims. Marvin Minsky famously said in 1970: “In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being.”

They were drunk on their own success. They had solved algebra word problems and checkers. How hard could translation and conversation be?

Turns out, really, really hard.

Part IV: The Prolonged Draught (1974-1980)

Here’s the problem with Symbolic AI: it’s incredibly inelastic.

It works great in a “micro-world”—like a chessboard or a specific math problem—where the rules are clear. But the real world? The real world is messy. The real world doesn’t have clear rules.

If you try to write a rule-based program to “recognize a dog,” you end up in a nightmare.

- Rule 1: Has four legs. (What about a chair?)

- Rule 2: Has fur. (What about a coat?)

- Rule 3: Barks. (What if it’s a quiet dog, or human that started barking for some reason?)

The researchers hit a wall. They realized that “common sense” reasoning wasn’t just a set of facts; it was a near-infinite web of context that they couldn’t program by hand.

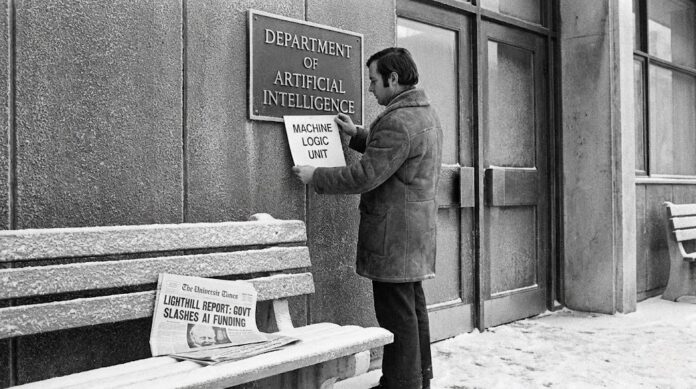

The Lighthill Report

In 1973, a professor named James Lighthill published a report for the British government. He basically looked at the last 20 years of AI and said, “This is all hype. You haven’t solved anything useful.”

The government listened.

Almost overnight, the funding evaporated. The “Golden Years” ended. This was the First Real AI Winter. It was a time of shame. If you were a computer scientist in the late 70s, you didn’t tell people you worked on “Artificial Intelligence.”

You told them you worked on “Machine Logic” or “Informatics” to avoid the eye-rolls.

Part V: The Expert Systems Boom (1980-1987)

Winter eventually eased up because corporate America realized that even if AI couldn’t simulate a human, it could simulate an expert.

Enter the era of Expert Systems. Instead of trying to build a general brain, they built specialized ones.

- Need a system to diagnose blood infections? Build MYCIN.

- Need a system to configure circuit boards for computers? Build XCON.

These systems were massive databases of “If-Then” rules derived from interviewing human experts. They were useful. They saved companies millions of dollars.

Japan jumped in with its “Fifth Generation Computer Systems” project, terrifying the West into pouring money back into AI. The industry boomed again. Lisp machines (specialized hardware for running AI code) became a hot commodity.

But history creates echoes. Just like in the 60s, the hype outpaced the reality.

Expert systems were expensive to build and impossible to maintain. If the rules changed, you had to rewrite the code. They couldn’t learn. They were just fancy lookup tables. By the late 80s, the market for specialized AI hardware collapsed.

The Second AI Winter set in. And this one was colder. It lasted through the early 90s. The term “AI” was dead again.

Part VI: The Quiet Revolution (1993-2011)

While the public stopped caring about AI, the researchers who stuck around changed their strategy. They stopped trying to program “rules” and started using Probability and Statistics.

This was the shift from “How do we tell the computer the answer?” to “How do we get the computer to calculate the likelihood of the answer?”

Deep Blue vs. Kasparov (1997)

This was the moment that brought AI back to the front page. IBM’s Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov, the reigning world chess champion.

It was a shock to the system. Kasparov accused the IBM team of cheating (he couldn’t believe a machine made such human-like moves). But Deep Blue wasn’t “thinking” in the way we do. It was just using brute force calculation, analyzing 200 million moves per second.

It proved a computer could conquer a domain of human intellectual superiority. But it still couldn’t tell you the difference between a cat and a dog.

The Rise of Big Data

But then something else happened in the 90s and 2000s: The (Real) Internet.

Suddenly, we weren’t starving for data. We were drowning in it. Images, text, logs, translations. This data was the fuel that a latent theory needed to finally catch fire.

Part VII: The Neural Network Renaissance (2012-Present)

To understand why modern AI (like ChatGPT or Gemini) exists, you have to understand the Neural Network.

The idea goes back to the 1950s (the Perceptron), but for decades, it was the underdog. The “Symbolic AI” people made fun of the “Neural Net” people.

Here is the difference:

- Symbolic AI: You tell the computer, “A cat has ears.”

- Neural Network: You show the computer 10,000 pictures of cats and 10,000 pictures of non-cats, and you let the computer figure out the patterns itself.

For a long time, Neural Networks didn’t work well because computers were too slow and we didn’t have enough training data.

But a few researchers kept the flame alive (Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun & Yoshua Bengio). They were the outcasts, working on “Deep Learning” when everyone else ignored them.

The Big Bang: ImageNet 2012

Every year, there was a competition called ImageNet to see which software could best recognize objects in photos. Usually, teams improved by 1% or 2%.

In 2012, a team led by Hinton used a Deep Neural Network (called AlexNet) and blew the competition away. They improved accuracy by over 10% in one go.

This was the “shot heard ’round the world.”

Suddenly, everyone realized: Wait, if we stack layers of these artificial neurons and feed them massive amounts of data using these new Graphical Processing Units (GPUs), they can learn ANYTHING.

This kicked off the era we are living in now.

- 2016: Google’s AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol at Go—a game so complex it has more possible board configurations than atoms in the universe. In Move 37, the AI played a move so creative and unexpected that it perplexed the human experts. It was the first time we saw a machine show “intuition.”

- 2017: A paper titled “Attention Is All You Need“ was published by Google researchers. This introduced the Transformer architecture.

The Transformer Era

The Transformer is the “T” in ChatGPT.

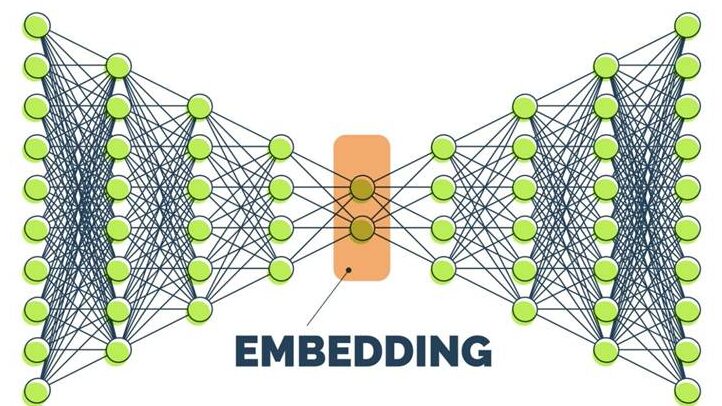

Before Transformers, AI struggled with language because it read sentences left-to-right. By the time it got to the end of a long sentence, it forgot the beginning.

Transformers allowed the AI to look at the entire sentence (or paragraph, or book) at once and pay “attention” to how words relate to each other, regardless of how far apart they are.

This architecture allowed researchers to train models on effectively the entire internet.

And that brings us to ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, Grok, DeepSeek and the Generative AI explosion. We moved from “Discriminative AI” (classifying things: is this a cat?) to “Generative AI” (creating things: draw me a cat in the style of Picasso).

Part VIII: Where We Are Now (and Where We’re Going)

So, here we are. We have systems that can pass medical boards, write code, and create art.

But are we in another bubble?

It’s possible. There is a lot of hype right now. Companies are slapping “AI” on everything, just like they did in the 80s. There are real concerns about hallucinations (AI making things up), copyright, and energy consumption.

However, this time feels different than the 1970s or 80s. Back then, AI was a promise. Today, it’s a utility. You use it when you unlock your phone with your face. You use it when Netflix recommends a movie. You use it when you ask ChatGPT to draft an email.

The “Black Box” Problem

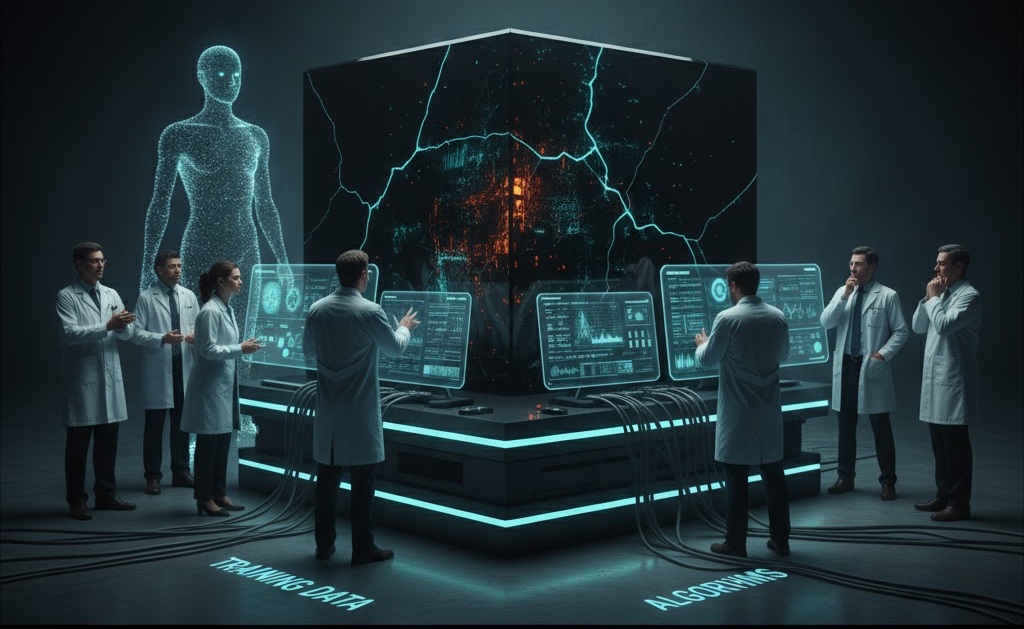

The irony of this history is that we’ve come full circle. In the 50s, we tried to build AI by writing clear rules we understood. Today, we have built powerful AI, but we don’t fully understand how it works.

We know the math, we know the training data, but the internal logic of a massive neural network is a “Black Box.” It’s opaque.

We have created the alien intelligence we were looking for. It doesn’t think like us. It doesn’t have our biology or our emotions. But it mimics us perfectly.

So, if you look at this 70-year history, a few patterns emerge:

- AI is cyclical: It goes through summers of hype and winters of disillusionment. We are currently in the hottest summer on record.

- Hardware drives software: The ideas for Deep Learning existed in the 80s. They only worked when we had the GPUs and the Internet (Big Data) to power them.

- We keep moving the goalposts: When AI conquers a task (like Chess or translation), we stop calling it “intelligence” and just call it “software.” This is known as the AI Effect.

The history of AI isn’t finished. In fact, if the pace of the last 5 years is any indication, the Introduction has just ended.

And the next chapter isn’t about building the digital mind; it’s about figuring out how to live alongside it.